Even though we fully support our research and recommendations, we do acknowledge that there are certain limitations such as availability of time and money to appropriately follow through with each recommendation. For example, some students may not be able to make time in their schedules for early morning exercise. Additionally, everyone responds to treatments differently, so some students may not be as receptive to certain recommendations, like sleep education, as others.

Category Archives: Facts

Why is This Important?

Today’s teen is busier than ever. With school, extracurriculars, homework, and more it is a rare moment that a modern high schooler is able to get an adequate amount of sleep. This lack of sleep is becoming an epidemic. Kids are falling asleep in class, cognitive ability is dropping, and memory is faltering.

As parents, teachers, and administrators it is a goal that children do their best and achieve all that they can achieve. This goal is only possible if circadian rhythm and chronotypes are taken into consideration.

This website is designed to give information to all the concerned adults that wish to help high school students succeed. Through this website, one should gain an appreciation for teenagers sleep-wake cycle and discover ways to balance and counteract the hectic cycle of teenage life.

How does stress affect sleep cycles?

In the red box you can see that the graphs look just about the same. One graph measured rhythms without stress and the other graph measured rhythms with stress. Because they are the same, the graphs show that stress does not affect the pituitary gland or sleep/wake cycles significantly. Proving the hypothesis incorrect.

Citation:

Razzoli, M.(2014). Chronic subordination stress phase advances adrenal and anterior pituitary clock gene rhythms. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology,307(2), R198-R205. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00101.2014

Goal:

The goal of the study was to show that stress unregulates the Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. This would show that the adrenal clock could be altered by stress.

Hypothesis:

The hypothesis of the study is that stress has a distinct impact on HPA axis regulation and other internal processes and effects pituitary clock rhythms. The gene rhythms were measured by assessing energy balances with body weight and food intake.

– The effect of chronic subordination stress was compared to locomotor activity. There was an increase in activity in the dark period and less activity in the light period in the CCS and control models. This trend rejects the hypothesis because CCS did not alter the activity in mice meaning that stress does not effect rythmic locomotor activity.

Findings:

The major findings were that stress triggered a phase shift in a clock gene rhythm. This lead to the idea that there is a link between desynchronized clocks and stress levels.

Question:

I would like to ask the author how much would stress affect a high school student’s performance on a test.

Sleep Insufficiency, Sleep Health Problems, and Performance in High School Students

In recent years, an increasing amount of research has been done on adolescent sleep deprivation. Sleep chronotype shifts with age; during adolescence, teens tend to go to bed later and wake up later when given the choice. Unfortunately, students often suffer from inadequate quantity of sleep due to their evening chronotype in combination with early school start times. Although adolescents typically need 9 hours of sleep in order to function properly, research shows that most students sleep fewer than 8 hours each night which “negatively [affects] academic performance, behavior, and social competence in adolescents” (Ming et al 72). Growing apprehensions about performance in school spurred research linking poor grades with adolescent sleep deprivation. However, little research has been done to confirm whether or not there is more than one contributing sleep issue. The goal of this study is to examine the multiple factors that contribute to sleep deprivation and result in poor performance in school. Ming hypothesizes that unnatural sleep cycles adapt to fit with the school schedule, ultimately resulting in poor performance in school.

To collect data, Xue Ming and fellow researchers created an “anonymous questionnaire [consisting] of 13 categories of questions regarding sleep habits and schedules, symptoms of sleep disorders, school performance and school start time” (Ming et al 72). Students also noted their typical waking time and bedtime both on weekdays and weekends, grades, sleep regularity, as well as their own assessment of their “sleep adequacy” (Ming et al 72). In all, 2147 high school students from the state of New Jersey responded to the questionnaire.

The results indicated that Ming’s hypothesis was indeed correct; there is a link between poor academic performance and lack of sleep, as well as a link between “earlier start time [and] poorer sleep quality and quantity” (Ming et al 76). Ming concluded that even though temporary sleep deprivation bears little effects on academic performance and health, long-term sleep deprivation can severely affect grades and functioning. In these cases, students are not catching up on sleep on the weekends like many of their peers. Ming observed that circadian rhythm and later evening chronotype play a major role in the effectiveness and efficiency of the body. Because students are forced to wake up earlier than they naturally would, their academic performance is inhibited. Day to day activities affected by sleep adequacy/inadequacy and circadian rhythm include “decision making, memory, processing speed, selective attention, and vigilance” (77). Lastly, Ming explains that the issue of sleep deprivation can be combatted by educating high school students about the negative impacts of not getting enough sleep, as well as mandating later start times in high schools.

**This figure establishes the percentage of students that got the specified amounts of sleep on both weekends and week nights. The majority of students got 8 hours or less of sleep, which is significantly lower than the recommended 9 hours of sleep for high school-age students.

Work Cited

Ming, X. (10/2011). Clinical medicine insights. circulatory, respiratory and pulmonary medicine Libertas Academica. doi:10.4137/CCRPM.S7955

Circadian Rhythm in Regard to Food Consumption

The goal of this study was to determine if the presence or absence of food had an effect on the circadian patterns of mammals. The scientists who conducted this study believed that there would be a mild effect on thee circadian patterns of the rats studied. Activity was measured to determine the circadian. The food anticipatory activity was the unit of measure and allowed the scientists to compare the various cohorts with one another.

In all these graphs, the x-axis is made of time while the y-axis is made of activity. These graphs show the change in circadian pattern due to food consumption only being allowed at odd times. The rats were withheld food until the middle of the day, as such the rats began to wake up during the day to eat. Eventually this began to change their circadian pattern causing them to switch over from nocturnal to diurnal effectively confirming the hypothesis that food intake alters circadian rhythm. It was found that food intake changes the release time and abundance of various hormones. This alteration includes melatonin. Essentially, the rats were more likely to wake up and stay awake with a regular morning meal and the rats were more likely to sleep longer if a meal was presented only sporadically or not at all.

I would like to ask the author of this study if there is any evidence that a lunchtime and evening meal have different effects on activity.

Mendoza, J. (2007), Circadian Clocks: Setting Time By Food. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 19: 127–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01510.x

Time of day, intellectual performance, and behavioural problems in morning versus evening type adolescents: Is there a synchrony effect?

Olivia Howell

30 September 2014

Citation

Goldstein, D., Hahn, C., Hasher, L., Wiprzycka, U., & Zelazo, P. (2007). Time of day, intellectual performance, and behavioral problems in morning versus evening type adolescents: Is there a synchrony effect? Personality and Individual Differences, 42(3), 431-440. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

Goal of the study

The study ranked students from ages 11-14 based on their chronotypes and administered tests over the phone and possibly a follow-up test in a lab. The goal was to see how students’ results changed on tests when they were administered in the morning versus in the afternoon.

Hypothesis of the study

The hypothesis was that students who were tested during their preferred time of day (as indicated by their chronotypes test) would receive better results than students tested not at their preferred time of day.

What was measured in the study?

The study measured the results of both telephone and in laboratory administered tests of Vocabulary (“verbal ability”), Block Design (“nonverbal reasoning”), and Digit Span (“short-term memory”).

Figure

Figure description

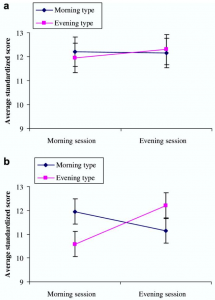

The two graphs show the correlation between the test scores (y-axis), the two different sessions (x-axis), and the morning/evening chronotypes (2 trendlines). As predicted, the morning types score higher in the morning sessions and the evening types score higher in the evening sessions.

Summary of the major findings of the article

The major finding of this article is that the time of day tests are taken influences the scores of students with increased morning performance in morning type students and increasing evening performance for evening type students. In general, the differences amoung test scores came from results in the Digit Span and Block Design sections suggesting that chronotype/time of day performance especially effects short-term memory and reasoning.

Question I would like to ask the authors of the article

I would like to ask the authors why they think vocabulary was not as affected by changes in session times.

Article link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1761650/